Global circulation patterns

At any time there are many weather systems weaving around the globe, however when averaged over many years a global pattern of air movement emerges.

Differential heating

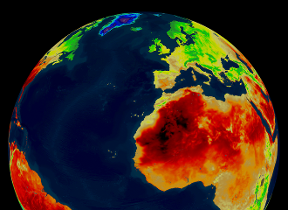

The reason we have different weather patterns, jet streams, deserts and prevailing winds is all because of the global atmospheric circulation caused by the rotation of the Earth and the amount of heat different parts of the globe receive.

The sun is our main source of heat, and because of the tilt of the Earth, its curvature, our atmosphere, clouds and polar ice and snow, different parts of the world heat up differently. This sets up a big temperature difference between the poles and equator but our global circulation provides a natural air conditioning system to stop the equator becoming hotter and hotter, and poles becoming colder and colder.

The global circulation

Over the major parts of the Earth's surface there are large-scale wind circulations present. The global circulation can be described as the world-wide system of winds by which the necessary transport of heat from tropical to polar latitudes is accomplished.

In each hemisphere there are three cells (Hadley cell, Ferrel cell and Polar cell) in which air circulates through the entire depth of the troposphere. The troposphere is the name given to the vertical extent of the atmosphere from the surface, right up to between 10 and 15 km high. It is the part of the atmosphere where most of the weather takes place.

Hadley cell

The largest cells extend from the equator to between 30 and 40 degrees north and south, and are named Hadley cells, after English meteorologist George Hadley.

Within the Hadley cells, the trade winds blow towards the equator, then ascend near the equator as a broken line of thunderstorms, which forms the Inter-Tropical-Convergence Zone (ITCZ). From the tops of these storms, the air flows towards higher latitudes, where it sinks to produce high-pressure regions over the subtropical oceans and the world's hot deserts, such as the Sahara desert in North Africa.

Ferrel cell

In the middle cells, which are known as the Ferrel cells, air converges at low altitudes to ascend along the boundaries between cool polar air and the warm subtropical air that generally occurs between 60 and 70 degrees north and south. This often occurs around the latitude of the UK which gives us our unsettled weather. The circulation within the Ferrel cell is complicated by a return flow of air at high altitudes towards the tropics, where it joins sinking air from the Hadley cell.

The Ferrel cell moves in the opposite direction to the two other cells (Hadley cell and Polar cell) and acts rather like a gear. In this cell the surface wind would flow from a southerly direction in the northern hemisphere. However, the spin of the Earth induces an apparent motion to the right in the northern hemisphere and left in the southern hemisphere. This deflection is caused by the Coriolis effect and leads to the prevailing westerly and south-westerly winds often experienced over the UK.

Polar cell

The smallest and weakest cells are the Polar cells, which extend from between 60 and 70 degrees north and south, to the poles. Air in these cells sinks over the highest latitudes and flows out towards the lower latitudes at the surface.

The Coriolis effect, winds and UK weather

Now we know about the Hadley, Ferrel and Polar cells, let’s take a look at how all that translates to what we see at the Earth’s surface. As a result of the Earth’s spin, each cell has prevailing winds associated with it, and we also have jet streams, all influenced by something called the Coriolis effect. This explains why air moves in a certain direction around an area of low pressure, and why trade winds exist. It also gives us an idea of why we see certain weather in and around the UK.

Warm moist air from the tropics gets fed north by the surface winds of the Ferrel cell. This then meets cool dry air moving south in the Polar cell. The polar front forms where these two contrasting air mass meet, leading to ascending air and low pressure at the surface, often around the latitude of the UK.

The polar front jet stream drives this area of unstable atmosphere. The UK and many other countries in Europe often experience unsettled weather, which comes from travelling areas of low pressure which form when moist air rises along the polar front.

Weather (or low pressure) systems bearing rain and unsettled conditions move across the Atlantic on a regular basis. The jet stream guides these systems, so its position is important for UK weather.

In summer, the normal position of the jet stream is to be to be north of the UK - dragging those weather systems away from our shores to give us relatively settled weather.

Normally the jet stream runs fairly directly from west to east and pushes weather systems through quite quickly. However, sometimes the steering flow of the jet stream can meander (a bit like a river), curving north and south as it heads east across the Atlantic. This is called a meridional flow, with the more linear west to east flow being called a zonal flow.

During a meridional flow areas of low pressure can become stuck over the UK leading to prolonged periods of rain and strong winds. During the winter the polar front jet stream moves further south leading to a greater risk of unsettled weather, and even snow if cold arctic air masses move south over the UK.

The continued effect of the three circulation cells (Hadley cell, Ferrel cell and Polar cell), combined with the influence of the Coriolis effect results in the global circulation. The net effect is to transfer energy from the tropics towards the poles in a gigantic conveyor belt.