Today (1 March 2024) is the first day of meteorological spring. We cannot yet guarantee exactly what this spring will bring, but wildlife will be betting on another warm one, writes Grahame Madge – a Met Office climate spokesman and wildlife enthusiast – ahead of the United Nations’ World Wildlife Day on Sunday.

The red admiral butterfly can now be seen on virtually any warmish day in the UK. Previously it wasn’t an over-wintering species and it only used to occur here in the warmer months as a visitor from further south. Picture: Grahame Madge

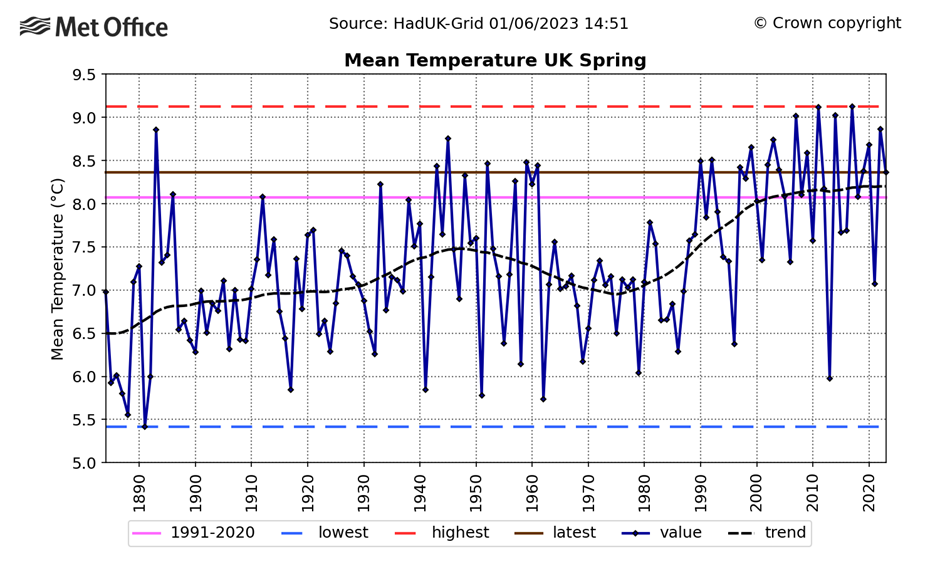

For the UK, the five warmest springs since 1884 have all occurred since 2007. Wildlife is responding to this shift towards warmer springs by accelerating their own activities.

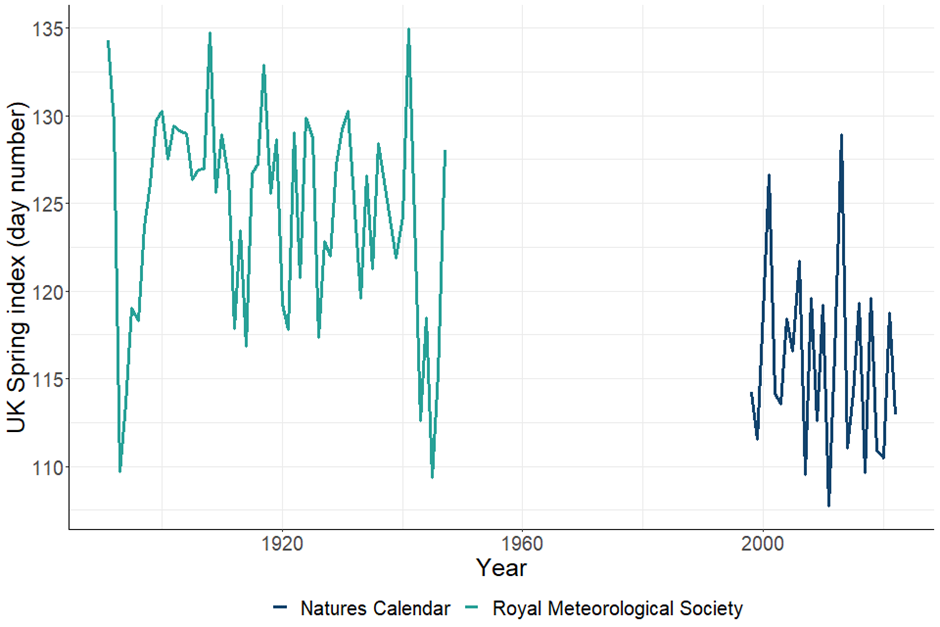

An index of spring – compiled from observations of the appearance of key spring wildlife species – is occurring many days earlier now when compared with the first half of last century.

The wildlife spring index shows the timing of biological spring events (the number of days after 31 December) in the UK. From 1891 to 1947 the Royal Meteorological Society provided the data, while from 1998 to 2022 it was provided by the UK Phenology Network (Nature’s Calendar, currently funded by the People’s Postcode Lottery, Postcode Green Trust). The Spring Index is calculated from the annual mean observation date of the following four biological events: first flowering of hawthorn; first flowering of horse chestnut; first recorded flight of an orange-tip butterfly; and first sighting of a swallow.

Already this year, at least one swallow has been reported in southern England; returning from Africa well ahead of the rest of its cohort. I have seen red admiral butterflies, bumble-bees and many chiffchaffs – a small usually summer-visiting songbird – in my corner of Exeter and sections of my walk to work have been lined with primroses. Anecdotally, these sightings are much earlier than I would expect.

However, my ad-hoc sightings in the margins of my dog-eared notebook are backed up by an army of wildlife fans diligently recording species across the UK through the Woodland Trust’s Nature’s Calendar scheme.

The recording of the timing of biological events is known as phenology. Two long-running nature surveys – monitoring four easily recorded species – have revealed that the average of time of appearance of these four species since 1998 is 8.7 days earlier than the average dates in the first part of the 20th Century. This is alarming, but not exceptional as other trends have been recorded too.

The dashed trend line in this graph shows that the UK spring has become more than 1.0°C warmer in the last 100 years.

A new course for the red admiral

The striking red admiral butterfly has always been a familiar visitor to parks and gardens the length and breadth of the UK. It used to be an exclusively migratory butterfly arriving on our shores after crossing the English Channel. But warmer winters are now altering this insect’s behaviour. Our winters are now becoming warm enough for it to overwinter as an adult to emerge on warm days in winter or early spring.

The warming of our climate is leading to a response from nature. The red admiral is an extremely abundant and seemingly adaptable insect, so it is unlikely to suffer any population consequences from this behaviour; at least at a species level. However, you have to wonder about the fate of those individuals encouraged to take their first flight of the year in winter, only to be hit by frost a few days later. What happens to them? My colleague Dr Mark McCarthy a Met Office climate statistics expert noted: “While frosts and cold spells in winter are falling, the date of first/last frost haven’t actually shifted all that much. So, although there are fewer frosts overall the risk of a ‘false spring’ in winter can increase the exposure to spring frosts later in the season. So, for parts of the environment and the agricultural and horticultural sectors there can be increased frost risks even with a declining trend.”

What happens when nature can’t rely on a warm spring?

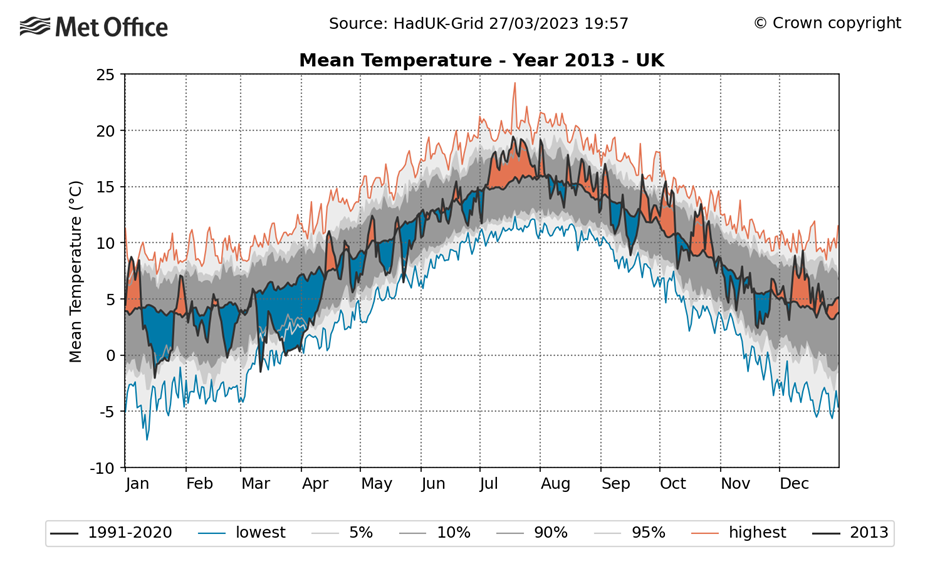

Many species are making the most of warmer winters and springs to gain an ecological advantage and make the most of the changing seasons. In fact, they are banking on the UK’s climate statistics showing that winter and spring are becoming warmer, on average. But these trends are derived from seasonal averages of temperatures observed over a standard three-decade period. Occasionally, the actual temperature can be a long way from the long-term average and wildlife can be caught out by a colder-than-average spring. This happened in 2013.

The spring of 2013 was the coldest in the UK in 50 years. Some species were severely impacted. Although not a common event, springs as cold as 2013 happened more frequently in the late 19th and early to mid 20th Century.

The stone-curlew is one of England’s rarest birds, with a small and vulnerable population in southern and eastern England. Picture: Adobe Stock

In 2013 I worked for the RSPB, and we were being besieged by members of the public reporting odd birds turning up in gardens desperate for food and respite from the cold. The greatest concerns for a conservation organisation were the fates of those species whose populations had become severely depleted by other factors. The number one species of worry was for the stone-curlew, a species of wading bird thinly spread across parts of the agricultural landscapes of southern and eastern England. The birds spend the winter around the Mediterranean and arrive back on their nesting sites in early spring. Farmers were reporting numbers of these birds which had succumbed to the cold because of a lack of food. At the time the RSPB’s conservation director Martin Harper said: “I can’t remember a spring like this – nature has really been tested by a prolonged period of very cold weather.”

During parts of March 2013, the average temperature in the UK dipped to their lowest levels.

Climate change is affecting many species of wildlife. Some will adapt and others won’t. But even those with potential to adapt may be confounded by other factors, and populations which are already depleted will be less resilient to climate change impacts.