Climate change drives increase in storm rainfall

Author: Press Office

00:01 (UTC+1) on Wed 22 May 2024

A new study has found climate change has influenced how much rain falls during autumn and winter storms.

Human-induced climate change made the heavy storm downpours and total rainfall across the UK and Ireland between October 2023 and March 2024 more frequent and intense, according to a rapid attribution analysis by an international team of leading climate scientists.

The 2023-24 storm season has been very active across the UK and Ireland. The countries were affected by numerous storms, 11 of which were named by the Western Europe storm naming group. With the naming of Storm Kathleen, in April, it was just the second time the letter K had been reached since the group was established in 2015.

Scientists from each of the National Meteorological Services that make up the Western Europe storm naming group (Met Office, Met Éireann and KNMI) were involved in the World Weather Attribution (WWA) coordinated study.

The study looked at the period from October-March, traditionally the peak of the storm season, and focused on Ireland and the UK. It did not use named storms as a storm indicator due to the relatively short observational record. To identify the stormiest days, the researchers used the Storm Severity Index (SSI), a metric that considers both strong winds and the size of the affected area.

Attribution to climate change

The scientists examined the influence of human-caused climate change on strong winds and heavy rainfall from these storms, as well as the rainfall totals from October 2023 – March 2024. They analysed weather observations and climate models to compare how these types of events have changed between today’s climate, with approximately 1.2°C of global warming, and the cooler pre-industrial climate, using peer-reviewed methods.

The scientists found that rainfall associated with storms is becoming both more intense and more likely. In a pre-industrial climate, rainfall from storms as intense as the 2023-24 season, had an estimated return period of 1 in 50 years. However, in today’s climate, with 1.2°C of global warming, similarly intense storm rainfall is expected to occur more often, about once every five years. Climate change has also increased the amount of rainfall from these storms, making them about 20% more intense.

If global warming reaches 2°C, storm rainfall could become a further 4% more intense and could occur about once every three years.

October to March rainfall

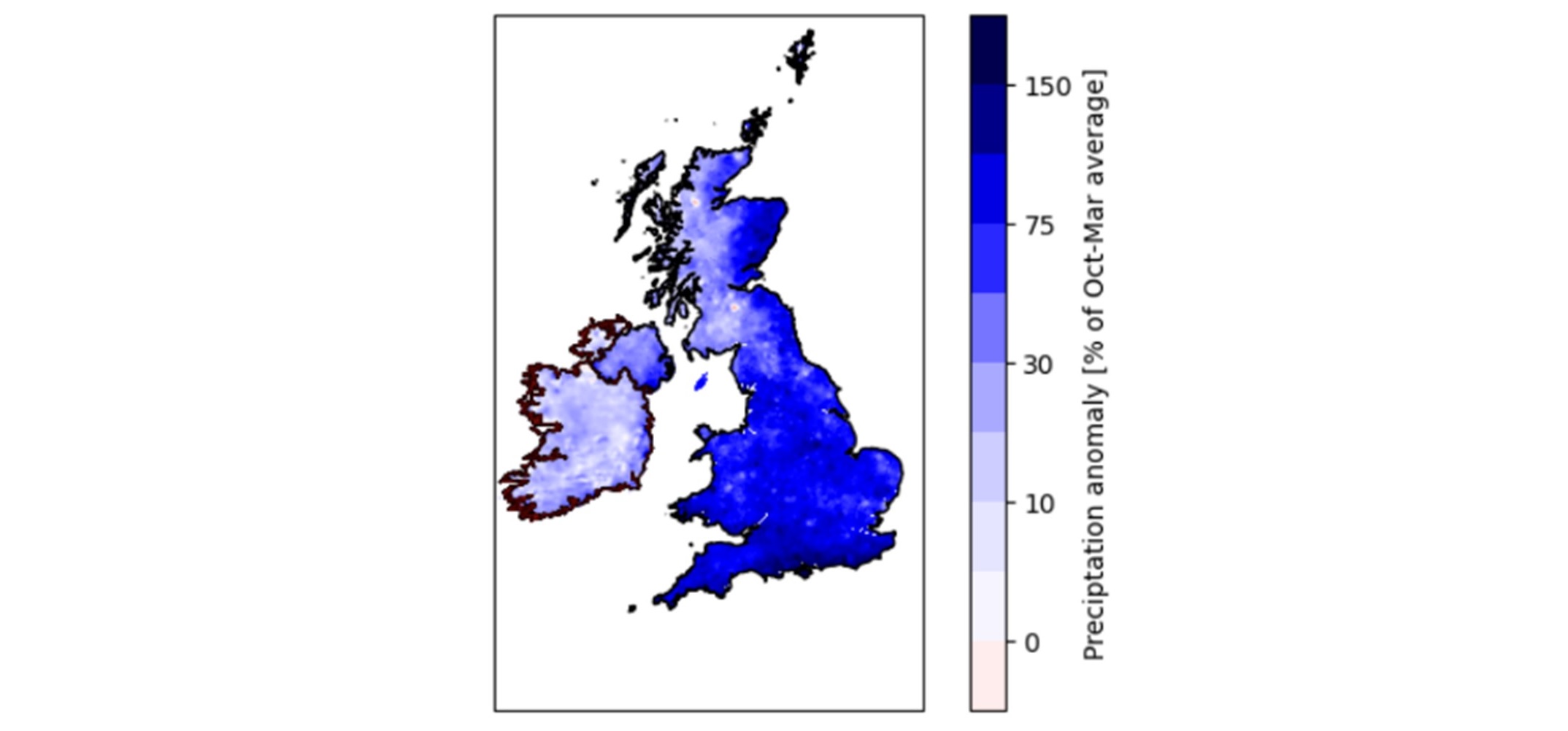

Given the major impacts of rainfall on farming and agricultural areas, brought by both severe storms and smaller weather systems, the researchers also looked at the total rainfall for the October-March period, which was the second wettest in the UK and the third wettest in Ireland.

Image: Seasonal precipitation anomaly [%] relative to the Oct-Mar average over the years 1991/92 to 2020/21. Source: Met Office HadUK-Grid and Met Éireann’s gridded precipitation datasets.

Climate change also had a strong influence on autumn and winter total rainfall. In a pre-industrial climate, wet periods such as the 2023-24 October-March season had an estimated return period of 1 in every 80 years. But in today’s climate, they have become at least four times more likely, expected to occur about once every 20 years.

The scientists estimate that climate change contributed to increasing the amount of total rainfall by about 15%. If global warming reaches 2°C, similar periods of rainfall that can saturate soils and cause large agricultural losses will become much more common, expected to occur about once every 13 years.

Met Office Science manager of Climate Attribution, Mark McCarthy, said: “The seemingly never ending rainfall this autumn and winter across the UK and Ireland had notable impacts across the two countries.

“This new study shows how rainfall associated with storms and seasonal rainfall through autumn and winter have increased, in part due to human induced climate change.

“In the future we can expect further increases in frequency of wet autumns and winters. That’s why it is so important for us to adapt to our changing climate and become more resilient to increases in rainfall.”

Impacts in Ireland

Ciara Ryan, Climatologist at Met Éireann, said: “This is the second attribution study looking at rainfall associated with storm events in Ireland this season and once again, we see an increase in the likelihood and intensity of the rainfall events as a result of human-induced climate change.

“Over the recent autumn-winter period we have witnessed the impact that heavy or prolonged rainfall has had on our communities, our land and the farming and agricultural sector, waterlogging the soils with virtually no time for them to dry out and become usable.

“The insights that we gain from studies like this are important to help us plan for the future, to support adaptation and mitigation strategies for an already changing climate.”

Less certainty on windstorms

The analysis found that average wind speed on stormy days has decreased slightly and could continue to decrease with warming. However, other studies using different datasets and climate models, or focusing on storm winds at different times of the year, have identified both small decreases or increases to strong storm winds with warming. This highlights the need for ongoing research into how climate change may influence the severity and frequency of windstorms in northern Europe.

Sarah Kew, Researcher at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, said: “While the influence of climate change on strong storm winds is less clear, autumn and winter rainfall has become much heavier, bringing more damaging and sometimes deadly floods to urban and agricultural areas.

Building resilience for extreme weather

Contributors from the British Red Cross provided an assessment of vulnerability and exposure within the scientific report. Ellie Murtagh, UK Climate Adaptation Lead at the British Red Cross, said: “We know from our work across the UK that flooding has a devastating impact on people’s lives. Its effects can be felt for months and years afterwards and those that are most vulnerable, people suffering from poor health or living in inadequate housing, are often hit hardest.

“Heavy downpours linked to climate change are making our winters wetter and flooding more likely. It is crucial we adapt and manage this risk. We will continue to work alongside the government, emergency services and other charities to protect our homes, our livelihoods and the most vulnerable in our communities.”